“Make it good…make it big…give it class.” – Louis B. Mayer, Co-Founder and Head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

The Hollywood studio system began in the 1910s and controlled most of the motion picture business until the 1960s. This period, commonly referred to as the “Golden Age of Hollywood”, was dominated by the “big five” studios: Loew’s Incorporated (parent company to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer), Fox Film Corporation (later 20th Century Fox), Paramount Pictures, RKO Radio Pictures, and Warner Brothers. These film studios were large conglomerates who managed all aspects of the movie business, from start to finish. Films were made in-house by these studios, using creative talent, on both sides of the camera, under long-term contracts. Rather than open casting calls, the studio could dictate which of its own stars would play roles. The same system applied to directors, producers, costume designers, etc. Furthermore, this system meant that studios not only controlled the production of films, but also the marketing and promotion for films. The “big five” studios also owned the film distribution and exhibition channels, including large networks of motion picture theatres.

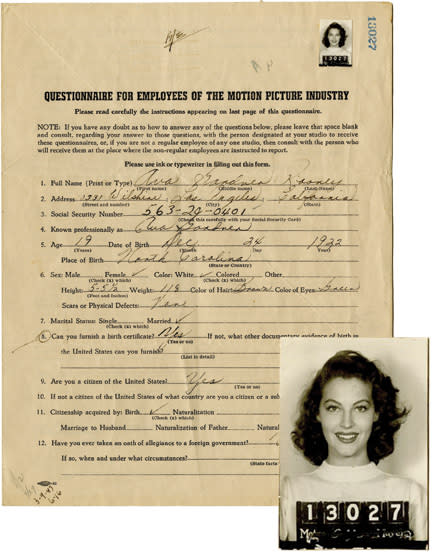

Ava Gardner’s studio "mug shot" and one page of her MGM employment questionnaire.

Following a series of antitrust investigations and competition from the rising popularity of television, the studios started to lose their command of the entertainment industry by the mid-1950s. The large studios broke up their conglomerates even as most of them remained major players in film production for many more years. While the studio system is now associated with such a prolific and beloved era in film history, it was created to funnel profits to those few at the top of each studio, a fact which drew criticism from inside and outside the system both during the years it dominated Hollywood and in the years since. At one time during the studio system, the film business was the 14th largest industry in revenue but was the 2nd in percentage of profits that its executives received.

A still from Ava Gardner's action screen test for MGM.

When eighteen-year-old Ava Gardner traveled by train from North Carolina to begin her film career, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was the number one studio in the world, a title it held for eleven consecutive years in a row (1931-1941). In her autobiography, Ava: My Story, Ava spoke frankly about her feelings and experiences with her home studio of MGM over the course of her contracted years (1941-1958). When she first visited the studio after arriving in Hollywood, she was still an awe-struck teenager, unaware of the ways her life would change or where her career would take her.

“The day began with a tour of the MGM lot in Culver City, a site that was definitely worth seeing. Twenty-three modern sound stages, great caverns of darkness as big as aircraft hangers, were spread out over a huge expanse of real estate that eventually grew to a hundred and eighty-seven acres. MGM had the world’s largest film lab; MGM had four thousand employees; ready and waiting for a director who might fancy it. But most of all, MGM had stars. ‘More Stars Than There Are in Heaven’, one studio ad claimed, and I sure as hell wasn’t about to argue. Other studios might have [had] better directors, or better writers, but MGM had the stars. …You name it, MGM had it [and] Louis B. Mayer, the man in charge, liked to think of the studio as one big family. … MGM films were always the glossiest, with the biggest budgets, best technicians and glamour so thick you could spread it on a plate. … If I was going to be anywhere in Hollywood, this sure seemed like the place to be.”

Ava’s first five years in Hollywood consisted mostly of bit parts or uncredited roles and an endless set of publicity photoshoots. Ava recalled in her autobiography, “I got fifty dollars a week, and, courtesy of a little firecracker embedded in my contract, the studio had the right to impose an annual twelve-week layout period during which my pay dropped to thirty-five dollars.”

In the book Living with Miss G, Ava’s personal assistant and life-long friend Mearene (Rene) Jordan recounted a conversation she shared with Ava about the early days of being under contract to MGM. “Don’t think you sat around just looking pretty at MGM; they worked you hard eight until five,” Ava said to Rene. “Mainly they used me for publicity stills which were distributed all over the country, you know, ‘girlie’ bathing suit stuff to help the war effort or at least give the boys a bathing suit treat. … I was wallpaper, Rene, wallpaper! A face in a crowd of teenagers, a dancer swirling on a crowded floor, someone walking down a street. MGM had scores of ‘starlets’ like me … [but] it was a constant turn-over. It was cheap labor; okay, it was a job. They trained you and nobody twisted your arm to sign the contract.”

MGM's 25th Anniversary Celebration, 1949. Ava is seated next to Clark Gable in the center second row from bottom.

During her MGM contract years, many of Ava’s best and favorite films were made through loan-out arrangements with other studios, a practice that greatly angered Ava. She said of her home studio: “Frankly, MGM was never the right studio for me. When I'd done The Bribe, it was my first starring role in [several] years there. The studio never bothered to package me. They never bought a property for me. In fact, they had so little interest in me they never wanted me around. The idea was, ‘Toss her out, lend her out, and give her away!’" She added, "But it was those loan-outs to other studios that infuriated me the most about my position at MGM. Even as my salary was rising (I was getting around fifty thousand dollars a year at this time, and it was to creep up higher) they lent me to other companies at salaries five and six times better than I was getting – and a percentage of the gross on top of that. They got well paid for giving me to those other studios, but I wasn't allowed to share in the wealth.”

As an example of the disparity in pay between star and studio, Ava was paid $200 per month for her work on The Killers while MGM was paid $1,000 per week by Universal Studios for her seven weeks of work. Twelve years later, Ava’s final film under contract to MGM was another loan-out called The Naked Maja. At this point in her career, she was making $90,000 under her studio contract, but, for the loan-out and a percentage of gross, MGM earned millions of dollars from Titanus Films, the company producing the picture.

During and soon after the “Golden Age”, the studio system also received critiques aimed at the quality of the films produced. These assessments included calling out the practice of block booking, wherein a studio would sell films to a theater as a unit, which usually consisted of five films. Only one of these films would be considered a particularly “good” film, referred to as “A-pictures”, while the other films were deemed of lesser quality and produced with lower budgets, commonly called “B-pictures”. Life magazine wrote in 1957 in a retrospective on the studio system: "It wasn't good entertainment and it wasn't art, and most of the movies produced had a uniform mediocrity, but they were also uniformly profitable.”

Critics of the studio system have argued that it created reliable revenue which in turn meant there was less incentive to try to make quality films. Ava Gardner’s critique of MGM’s treatment of her included similar indictments of the system. She felt that the studio did little to nurture and develop her acting skills.

In her autobiography, she recalled, "except for Lillian Burns from time to time, I only remember a single example of someone caring about the quality of my work. In the breaks during the filming of The Bribe, Charles Laughton, one of my costars, used to take me aside and read me passages out of the Bible, then make me read them back with the right cadences and stresses. He was a brilliant classical actor absorbed by his craft and loving it. And he was the only one in all my film years who took the time and went out of his way to try and make an actress out of me. … In fact, if Metro did anything, it was to stand in the way of my learning anything. I remember Greg Peck asking me if I wanted to do a part in a play they were doing in La Jolla, just to work out, to learn. ‘Okay,’ I said, ‘if I can start with something very small.’ But before I could commit I had to ask Metro. ‘Small part? Not the lead? Of course you can't do that,’ I was told. ‘You either play the lead or nothing.’ ‘But I can't possibly play the lead,’ I said. Little did they care. And that was the last time I allowed myself to even think about learning on the stage.”

Contracts for studio stars aimed to control not only the actors' careers but also their private lives away from the confines of the studio. Ava detested this aspect of her contract. In her autobiography, she said, “I had to make personal appearances for publicity purposes, or for any other reason they could think up, anywhere they chose. Travel anywhere MGM felt like sending me. But I could not ever leave Los Angeles, even when I was on vacation, without their permission.” In a letter published in Grabtown Girl, a biography of Ava’s early life and North Carolina connections, Ava wrote a friend back in North Carolina in 1944 that she wished she could go home to visit, “but the studio won’t let me just now. I’m hoping to go next fall.”

The studio contracts included strict morality clauses as well. MGM’s contract included language that a star could not “do or commit any act or thing that will degrade her in society, or bring her into public hatred, contempt, scorn, or ridicule, that will tend to shock, insult, or offend the community or ridicule public morals or decency, or prejudice the producer or the motion picture industry in general.”

When Ava and Mickey Rooney decided to get married, as they were both under contract with MGM, they had to have permission from the studio head, Louis B. Mayer, to do so. Ava said of the morality clause in her contract, “I decided from the very first that the contract abused my sense of personal human rights. We were told what to do, when to do it and how, and we were paid very little. … I decided from the first that I had the right to act according to my own principles. And if mine clashed with theirs, and they didn’t like it, that was not going to be my problem.”

Ava called the atmosphere at MGM “stifling, killing” when she recounted how they responded to her political activism. She said, "When I appeared for Henry Wallace when he ran for president in 1948, Mr. Mayer called me in and told me I had to stop. He told me that Katharine Hepburn had ruined her career doing things like that. They liked to terrify you, to threaten that if you didn't do what they said, they would ruin your career, too. And they could do it. No one ever thanked me during all those years when I was the good girl on the lot.”

The studio system’s demise began in earnest in 1948 when the federal government filed an antitrust suit against the “big five” studios. The Supreme Court ruled that the studio conglomerates were in violation of antitrust laws. The remedy was for the companies to separate production from distribution and exhibition (theatres). Interestingly, Ava Gardner’s long-time friend and admirer Howard Hughes was involved in breaking up RKO Radio Pictures. As the head of the studio, he entered into an agreement with the federal government to divide the company into two parts (production and theatres) and sell off one part eventually. Other studios soon followed suit.

At the 1974 premiere of That's Entertainment.

Before the end of her MGM contract, Ava returned from her home in Europe to visit the studio where her career began. Rene drove over to the MGM lot with her and remembered the experience in her book Living with Miss G.

“Miss G and I took a trip to see how MGM studios were faring out in Culver City. Half the studios were empty, and they told us it was the same at Warner, Paramount, Universal, and all the other major studios. ‘Christ, Rene,’ said Miss G. ‘At least we saw the best of it. Who’d have expected fabled Hollywood to close down like this?’ Of course, it didn’t. Movie-making was simply moving into the hands of independent producers and independent stars. They were making movies all right, particularly in Britain, France, Italy and Spain. Hollywood never really returned to the eminence it had [once] held.”

Ava recalled about making her final film under contract to MGM, “The Naked Maja was the last picture I had to do on my damn MGM contract. When it was over I was free at last – free to choose my own projects, free to command the kinds of fees I was worth. It was about time.” The first project she completed as an independent star was On The Beach (1959) with director Stanley Kramer and one of her favorite co-stars, Gregory Peck. Ava spent the remainder of her life working independently, more selective with chosen projects and working on her own terms.

Ava summarized her thoughts on MGM studios as such: "They may have found me, but I came to feel I owed them, and the business they represented, nothing at all."