The film 55 Days at Peking (1963) takes us to Peking (now Beijing), China in the year 1900 at the time of the Boxer Rebellion. Ava Gardner stars as Russian Baroness Natalie Ivanoff, the love interest of the lead male character played by Charlton Heston, Major Matt Lewis. David Niven and Flora Robson also appear in the large cast, which included thousands of extras. While this historical epic visually captured the intensity of the Boxer Rebellion, the filmmaking process and the final results were disappointments for many involved, including Ava. The movie was also a disappointment in the eyes of many critics for its historical inaccuracies, underdeveloped characters, and for what many viewed as subpar dialogue.

Ava was convincing as a Russian aristocrat, whose sumptuous jewels are the envy of all the dignitaries’ wives. Her character undergoes an impressive transformation. Later she dons a nurse’s uniform and pawns her precious jewels to provide medicinal relief to the victims of the siege before getting killed in action.

The Boxer Rebellion was a government-supported uprising against foreign and colonial powers as well as Christian influences in China. The so-called “Boxers” were ultraconservative Chinese citizens who were against these rising influences coming into China. They saw foreigners, taking Chinese land and introducing Christian evangelism, as threats to traditional Chinese culture. Their rebellion received support and approval from Empress Dowager Cixi. The rebellion included a 55-day siege of the diplomatic Legation Quarter where foreign embassies were located and where many foreigners as well as Chinese Christians, were forced to take refuge when the Boxer Rebellion began.

While the film was set in Peking, China at the turn of the 20th Century, it was actually filmed in Spain in 1962. To recreate the Peking of 1900, the producer, Samuel Bronston, had huge sets constructed on a 70-acre barley field approximately 15 miles outside of the city of Madrid. The numerous reconstructed structures, which were best viewed from the air, were completely surrounded by a canal and a 40-foot-high wall. To populate the set, the producer hired more than 6,500 Chinese residents of English, France, and Spain. To further invoke the place and time, the Chinese American watercolor artist Dong Kingman painted elaborate historic scenes to open and close the film.

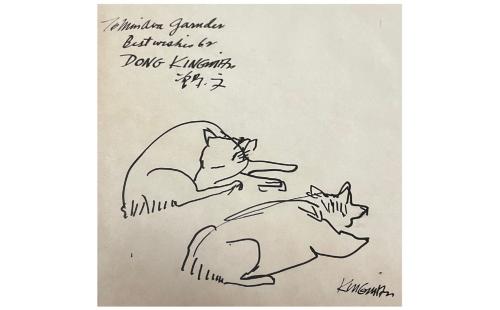

Artist Dong Kingman drew this sketch of two dogs for Ava Gardner during filming of 55 Days at Peking. The sketch is on loan to the Ava Gardner Museum from Ava Thompson, Ava Gardner’s great niece.

Bronston made several historical epics before and after 55 Days at Peking, including King of Kings (1961), El Cid (1961), The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), and Circus World (1964). The popularity of these films was starting to wane with moviegoers by the early-to-mid 1960s. As a result of decreased audience share, the cost of producing epics was becoming prohibitive. When 55 Days at Peking began shooting, these concerns were apparent, and, with a price tag of between $4-5 million, the pressure to create a hit loomed over the production.

Bronston’s production studio in Spain was built to accommodate the large numbers of actors, gigantic sets, and countless crew members – all the things that filmmaking on an epic scale required. Much of the city of Peking was recreated on set, even though most of it never appeared in the final film. The concrete structures were built to impress any VIPs that visited the enormous set; however, Charlton Heston claimed that the crew "never turned a camera on two-thirds of this incredible city." In addition to building elaborate sets, the production also brought in thousands of Asian extras. Many of the extras had no professional film experience, instead they were recruited from Chinese restaurants and laundries around Spain as well as other European countries.

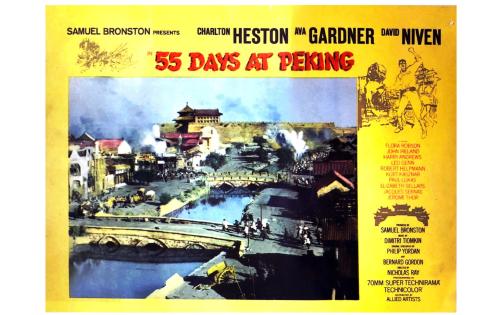

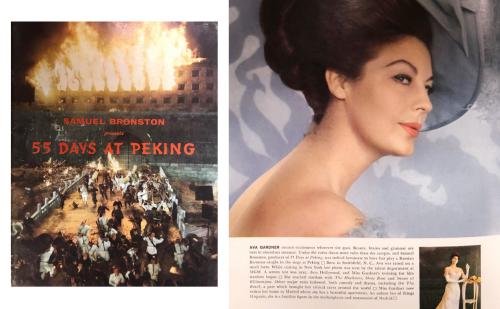

Lobby card for the film depicting the city of Peking under siege.

The film was meant to be a grand spectacle, and, in many ways, it delivered on that promise. Shot on 70mm with exciting action and battle sequences, stunning costumes, and a star-studded cast of established performers in the lead roles, on paper, the film was poised to be a huge success. The film was one of many epics made in the 1950s and 1960s meant to be viewed on the newest wide-screen technology. Critics praised the film for its “lusty vigor and infectious excitement.” A New York Times critic called the film “rousing, sometime exciting, action fare.” A Variety critic applauded the film’s "uncommon visual excitement" and Jack Hildyard's "excellent" photography. Time’s critic highlighted the pictorially “magnificent” film's lavish production values including its $9 million budget, 6,500 extras, and the high cost of replicating Peking to only then blow it all up. Many critics repeatedly praised the film’s fireworks, with the New York Times claiming that “the film remains in memory for its flashing movement and fireworks.” The New York Times critic went on to say, “The producers were sensible enough to keep the dialogue, which is often banal, to a minimum. Although it was all done in and around Madrid, the sound and fury and beauty of these momentous ‘55 Days at Peking’ are brought vividly to life. Most of the principals and their stories are not.” This critique praises the historical epic’s ability to bring a visually stunning reproduction of 1900 Peking to the screen; however, it also summarizes the criticism leveled at the film for its characterizations and dialogue.

Many, including Ava Gardner, were disappointed with the final film. From the very beginning, the production was plagued with issues. When the principal cast and crew arrived in Spain, Ava hosted a cocktail party for everyone at her Madrid apartment. All attendees got along well at the event, and, with this comradery, the production seemed to be off to a great start. However, as the rehearsals and filming got underway, Gardner and her costar Charlton Heston did not get along particularly well.

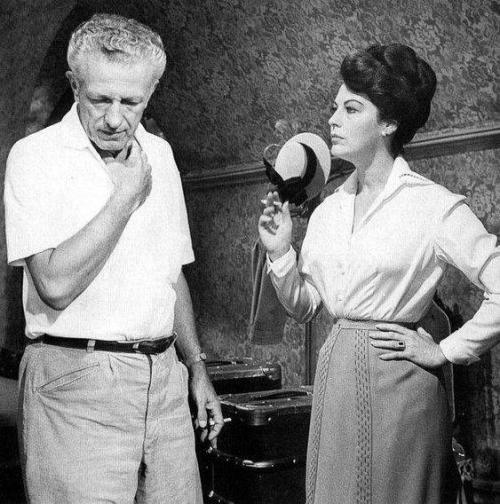

Director Nicholas Ray with Ava Gardner on set. Ray’s biographer Bernard Eisenschitz wrote, “Ray particularly enjoyed directing Ava Gardner with whom he formed an alliance of outsiders.”

The director, Nicholas Ray, had worked successfully in Hollywood for many years and created such noted films as In a Lonely Place (1950) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955). These were smaller, more intimate films, so Ray was not accustomed to leading big budget epics. Midway through the project he suffered a heart attack and left the production. The film was finished by two different directors working on separate parts of the film. Andrew Marton, a specialist in action and adventure sequences in epic films like Ben-Hur (1959) and The Longest Day (1962), took over the remaining work on the big battle scenes. At the recommendation of Heston, director Guy Green flew over from Hollywood to complete the filming of some of the intimate character scenes. From all accounts, the cast worked well with both of Ray’s replacements.

The script was not finished at the start of filming, in fact, it was largely in shambles. Many key scenes were written just the day before they were shot. The principal actors found themselves being handed small pieces of paper with bits lines piecemealed together that they had to memorize on set. In some instances, both David Niven and Charlton Heston even resorted to making up their own dialogue so the shooting could continue to progress. Ava found all of this disorder and unprofessionalism on behalf of the production team to be very unsettling. As a result of this chaos, the dialogue suffered, the characters were not fully realized, and the film lacked historical accuracy.

Ava Gardner’s copy of the production script.

The film was opened in London in early May 1963. A few days later, it screened at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival, and was received coolly at the event. The movie came out at a time in Ava Gardner’s career in which she was taking on fewer projects. In fact, the role was her first after a 2.5-year, self-imposed hiatus in the early 1960s. It was also the only film Ava ever made in Spain while she was living there. She was no longer under contract with MGM and was able to make her own career decisions. Ava was initially intrigued by the story. She was reportedly paid $500,000 to play Baroness Ivanoff, an exiled aristocrat with a troubled past who sacrificed her wealth and life for others, a part that sounded interesting on paper. However, it didn’t live up to her expectations. Ava was particularly disappointed with the written dialogue and the underdevelopment of her character.

Adding to matters, Ava Gardner and her costar Charlton Heston did not see eye-to-eye. In fact, Heston had lobbied against Ava receiving the role in the first place. Heston wrote in his diary in May 1962: “Nick [Nicholas Ray, the director] phoned from Spain with disturbing news: It seems they want to use Ava Gardner. I’d better get my ass over there next week and find out what the hell is happening.” However, producer Samuel Bronston and director Nicholas Ray overruled his complaints, knowing that the film needed Ava’s name and star power in order to have a better chance at the box office.

Ava was also unhappy with the use of large numbers of extras that were not professionals accustomed to demands of Hollywood sets. Crowds of untrained extras around meant unauthorized photos taken of Ava, which greatly upset her. Also, in the filming of one scene, Ava was nearly trampled by a group of rioting extras who weren’t being directed properly to know where she would be in the scene. Like many of Ava’s characters, Baroness Ivanoff was killed off before the end of the film – dying after suffering an injury while attempting to smuggle medical supplies to those who needed them. According to Ava Gardner’s personal assistant and friend Mearene (Rene) Jordan, Ava was happy to have an early exit from the film: “‘Fifty-five days!’ shrieked Miss G. ‘It felt like fifty-five years!’”

A comic book version of the film’s plot.

Rene summarized the filming experience in her book, Living With Miss G: “The characters were cardboard, the script ridiculous, and the sets secondhand, having been used in a previous Sam Bronston Roman epic that had been produced in Spain. The first director, Nicholas Ray, had a heart attack and had to be replaced. The superb cast members: Charlton Heston, David Niven, Flora Robson, Robert Helpmann, John Ireland, Paul Lukas, Leo Genn and Elizabeth Sellars, all wandered around trying to work out how they had managed to get themselves stirred into such an epic stew.”

Ava Gardner’s niece Mary Edna Grantham recalled visiting her Aunt Ava on the set of the film. Mary Edna and her husband Brick got to witness firsthand how hard Ava worked on set, preparing her lines and arriving at set early in the morning. Mary Edna remembered Ava introducing her and her husband to Charlton Heston and his family as well as others in the cast and crew. Mary Edna later recalled entering Ava’s dressing room once: “She had on a beautiful gown. She was into chess at the time, and she had a chess board set up in a corner of the dressing room. She also had music playing that would help her stay in the mood of her character.”

Ava did not write about the film in her autobiography except to say that “the three pictures I'd done since On the Beach – The Angel Wore Red, 55 Days at Peking, and Seven Days in May – didn't exactly make me bubble over with enthusiasm at the thought of getting back in front of the camera.” It is likely that Ava’s negative experience with the film contributed to her decision to turn down several other high-profile roles in the years that followed including in Sweet Bird of Youth (1962) and The Pink Panther (1963).

Promotional materials for the film.

While Ava was less than enthused with the film, there were some positives found by many film critics. While some of them agreed that the dialogue suffered, the epic was applauded for its success in capturing vivid scenes and bringing the Boxer Rebellion to life on the big screen. In the end, most reviewers felt the impressive special effects and sets were the real stars of the production and the human elements were overshadowed by the film’s epic grandeur.

An article from Turner Classic Movies summarizes the way critics look back at the film today: “It's hard to deny that 55 Days in Peking is short on psychological depth and historical accuracy, and the dialogue contains the kind of insensitive racial comments that have become mercifully rare today. Still, the visuals are as arresting as ever. It's no wonder that reviewer after reviewer has praised the spectacular fireworks, especially at the climax, and the movie vividly represents a bygone age of international spectaculars that made up in extravagance what they sometimes lacked in coherence and common sense."

This blog post is part of Hometowns to Hollywood's fall blogathon, Celluloid Road Trip Blogathon: International Edition.