This post is part of the Classic Movie Blog Association’s fall blogathon: Movies are Murder.

Throughout her five-decade career, Ava Gardner often played complicated, emboldened women. Beautiful, but dangerous and mysterious. Adored, but seeking more fulfillment. Glamorous, but also intelligent and ambitious. Several of these on-screen characters were murdered or killed. In the 1940s and 50s, these cinematic deaths were usually tied to matters of morality under the Motion Picture Production Code (commonly called the Hays Code for administrator Will H. Hays). When analyzing the dark fate of her more tragic characters, a pattern starts to emerge to the types of women Ava depicted and to the aspects in their personalities that ultimately lead to their untimely end.

Much of Ava’s time in Hollywood coincided with the Hays Code, which was in effect for three decades during the height of the studio system. The code, which was written in 1930, was strictly enforced between 1934 and 1954, gradually weakening afterwards and becoming obsolete by 1968. During the code’s heyday, it put restrictions on cinematic depictions of several topics like sexual intimacy, homosexuality, interracial marriage, nudity, and illegal drug use. It also stipulated how other issues needed to be addressed, such as infidelity, violence, and alcoholism. For example, actors could not be shown drinking liquor unless it was deemed “necessary” for the plot or characterization, and its use could not be represented in a positive light.

In general, the production code’s goals were to prevent any film from “lower[ing] the moral standards of those who see it” and to show the "correct standards of life." Films were to ensure that any law was respected and no “sympathy be created for its violation.” In other words, the audience must always side with morality and never be encouraged to feel sympathy for anyone committing “crime, wrongdoing, evil, or sin.”

The Hays Code was developed in response to several high-profile controversies involving alleged sexual misconduct, illicit drug use, and even death in the Hollywood community. These scandals garnered considerable pushback from the public and government alike. Many municipalities began censoring films for the industry’s perceived lack of morals. Hollywood executives decided to take matters into their own hands through self-censorship. By creating and adopting a unified Motion Picture Production Code, the movie industry standardized the rules and guidelines for all markets, so their films did not require different editing for different locales.

“Didn’t anyone tell you that tits aren’t allowed in a Hollywood film? It doesn’t matter how beautiful they are, it’s immoral and indecent…Do you want us to be accused of corrupting the whole of America?” – Ava Gardner on the reaction to the nude statue sculpted of her for One Touch of Venus (1948), Ava: My Story

The Hays Code’s influence on the industry was especially evident in the storylines within the film noir genre. These films often followed common plot elements featuring a “dangerous” woman (femme fatale) who takes the main male character down a path of doom and destruction – seducing him into a life of crime or leading him to his own death. The code required that an “amoral” femme fatale had to also meet her own demise by a film’s conclusion – either by imprisonment or death. The development of the femme fatale archetype coincided with changes in the real-life roles of women in society. During World War II, women increasingly entered the workforce, and, upon experiencing the financial freedom and mental stimulation of a career, many did not want to return home to solely a domestic life at the war’s end. This shift in gender roles and responsibilities caused anxiety in some men. Thus, the film noir capitalized on those male anxieties by depicting smart, cunning women who were punished for their actions, insinuating that women who did not conform to traditional gender roles were immoral, dangerous, and should be chastised.

The Hays Code’s impact can clearly be seen in the fates of several of Ava’s characters in the 1940s and 50s. Ava often played roles that went against the mold of traditional gender roles, and, as a result, they were often met with unhappy ends. Ava was also cast in roles where her beauty was, on the surface, the most important thing about her character. However, through her skill as an actress, Ava added nuance to these portrayals, imbuing her characters with quiet intelligence and strong self-awareness. Her characters knew they were beautiful and understood the power that beauty wielded over men, but her characters also displayed ambiguity to physical appearance and instead sought deeper, emotional connections.

By looking specifically at instances where Ava’s characters were murdered or killed by others (including being a casualty of war), we can see the influence of the Hays Code and also how the time period’s morality standards and gender dynamics played a role in determining her characters’ fates.

Murdered

Two films in which Ava’s characters were murdered both involve infidelity being punished with death.

Mistress Isabel Lorrison (Ava Gardner) and wife Jessie Bourne (Barbara Stanwyck) meet in one scene in the film.

East Side, West Side (1949)

In East Side, West Side, Ava Gardner portrays Isabel Lorrison – “the other woman.” She is a fashion model who, after having an affair with a married man named Brandon Bourne (James Mason), tries to win him back even after he has returned to his wife, Jessie (Barbara Stanwyck). Ava’s character is murdered off-screen, and, when her body is found, both her lover Brandon and his wife Jessie are considered the prime suspects. After it turns out that Isabel was actually killed by the jealous girlfriend of a man she once took as a date to an event, Jessie decides to leave Brandon. This conclusion wraps up the film so that those responsible for ruining a marriage (Isabel and Brandon) are both punished, and the wife gets to start anew with someone else.

The Hays Code dictated that consequences were necessary for “bad” behavoir. The code stated: “Adultery and illicit sex, sometimes necessary plot material, must not be explicitly treated or justified, or presented attractively.” East Side, West Side provides the ultimate warning – cheaters might end up dead. While the film is not a film noir it does contain some elements of the genre – adult and sinister themes, an urban setting, a femme fatale who leads a man down a dark path, and atonement for immorality.

This lovely dress from our permanent collection was designed by Helen Rose for Ava’s role as Isabel Lorrison in East Side, West Side.

The Barefoot Contessa (1954)

The Barefoot Contessa follows a “rags to riches” story with cautionary lessons about the hardships of fame. The film offers a scathing critique of the Hollywood star-making machine. The story begins and ends at the funeral of Maria Vargas, a once little-known Spanish dancer who achieves sudden fame in Hollywood after being discovered by a down-and-out writer-director named Harry Dawes (Humphrey Bogart). Although she becomes a successful film star, Maria remains unfulfilled and resentful because she must constantly answer to the rich, arrogant men who permeate the film business and want to control both her career and personal life. She ultimately finds love when she meets and marries Count Vincenzo Torlato-Favrini (Rosanno Brazzi), but their happiness is short-lived when he too deceives her. Vincenzo is impotent due to a war wound, and he waits until their wedding night to tell Maria. Despite this heartbreaking news, Maria still deeply loves her husband and wants to make him happy. In a bid to produce an heir for his lineage, Maria sleeps with their chauffeur. Consumed with jealously upon discovering the affair, Vincenzo kills her and her lover without ever knowing that she was pregnant or the reasons why she had an affair.

This lobby card in the Museum's collection shows the scene in which Maria’s dead body is carried out by her husband Vicenzo after he has killed her.

Ava describes the film’s plot in her own words in Ava: My Story: “The count was in the wrong place at the wrong time during the war and has to tell his bride that ‘Almost the only undestroyed part of me is my heart.’ Maria is distraught, but thinks she knows a way out. She’ll have an affair with the count’s conveniently available chauffeur, present her husband with a much-wanted heir, and everyone will live happily ever after. Unfortunately this count is very much the jealous type. He kills both Maria and the chauffeur, and at the film’s close he is led, handcuffed, off to jail.”

This portion of the plot involving the extramarital relationship and resulting violence plays out just as expected under the requirements of the Hays Code and within a climate of male anxiety and insecurity. The affair and subsequent murders are punished so that neither act can be interpreted as “correct standards of life” even if the audience may sympathize with the complicated motivations and intentions of the characters. The cheating wife dies, and the murderous husband is imprisoned. Maria’s friend and mentor, Harry, knows the complete truth, but decides to keep it a secret from Vincenzo – an act which seemingly protects Vincenzo’s fragile sense of manhood. The fate of these characters also furthers the film’s point about the price of stardom, which aligns with many of the attacks and critiques of Hollywood’s moral character.

Original artwork for the poster for The Barefoot Contessa, part of the Ava Gardner Museum’s permanent collection.

Casualty of War

The films in which Ava’s characters were killed in a wartime setting each involve a sort of redemption through death. These characters are given the opportunity to atone for past “mistakes” or “sins” through the ultimate sacrifice. Some of these films were made as the power of the Hays Code started to wane – being less enforced and providing more leeway or grey areas in how social morals were depicted on screen.

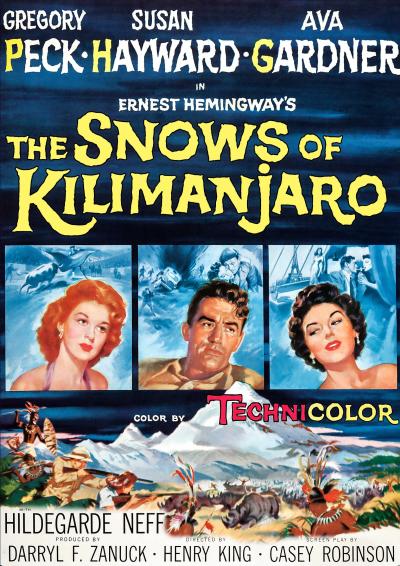

The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1952)

In The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Ava’s character, Cynthia Green, is not murdered outright, but is instead a casualty in the Spanish Civil War. In the film, Cynthia, who works as an ambulance driver, is the ex-wife of the main character Harry Street (Gregory Peck). The two begin their relationship passionately in love, but their marriage soon deteriorates. Cynthia learns she is pregnant as Harry realizes he wants more freedom out of life.

Poster from the film The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

As Ava put it in her autobiography, “Finally, fearing that a family would tie him down and ruin his career, I [Cynthia] deliberately fall down a pretty fearsome set of stairs and miscarry. Then, to get me off his mind, I make him believe I’ve fallen for a fairly sappy flamenco dancer. He remarries. I don’t reappear in his life until a decade later, when as an ambulance driver in the Spanish Civil War, I just about die in his strong arms.”

Cynthia, while the love of Harry’s life, causes her own miscarriage and leaves her husband for another man – freeing Harry to live the life he claims to want. Due to Hollywood’s code of morality at that time, Cynthia must be punished for her “immoral” acts – abortion and adultery – no matter her own justifications or motivations. Her acts are in complete sacrifice and service to the male character – acts that only the audience fully understands. Her character is given some redemption in the end when she dies serving during wartime. .

The Angel Wore Red (1960)

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, enforcement of the Hays Code was increasingly less prevalent. By 1968, it was completely abandoned for the new Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) rating system which still exists today. In The Angel Wore Red, also set during the Spanish Civil War, Ava portrays a cabaret performer and prostitute named Soledad who falls in love with a fallen priest, Father Arturo Carrera (Dirk Bogarde). Father Arturo has recently left the church over its position on the civil war. When priests and churches become targets during the war, Soledad offers him protection even though their involvement leads to her imprisonment and eventual death. The film’s plot revolves around a church relic that both factions want to possess in order to ensure victory in the war. Soledad helps Father Arturo hide the relic, before being wounded and later dying. However, later, the relic is needed to prove Father Arturo’s loyalty to the faction more sympathetic to the church. The relic is revealed in time to demonstrate that Father Arturo is telling the truth, thus sparing his life and the lives of other prisoners of war.

A poster for the film emphasizes Ava's character and her profession.

While less enforced by 1960, the code’s far-reaching influence over the morality in films can still be seen in the way the plot of The Angel Wore Red develops and plays out. Ava’s character is redeemed by her actions to help the priest; however, her death also serves as a form of punishment for prostitution and perceived immorality.

55 Days at Peking (1963)

55 Days at Peking finds Ava once again portraying an unfaithful wife. Set during the Boxer Rebellion in China, the film revolves around the attack on foreigners, which was encouraged by the Dowager Empress Cixi. Ava plays Baroness Natasha Ivanova, a Russian aristocrat. Her character once had an affair with a Chinese general, which in turn causes her Russian husband to commit suicide. She tries to flee when the attack begins; however, she is unable to leave. She eventually volunteers in the hospital caring for the wounded and injured. She sacrifices her own valuable jewelry in exchange for much-needed food and medical supplies. During this act of self-sacrifice, she is fatally wounded, dying shortly thereafter.

Ava’s role in 55 Days at Peking follows now familiar storylines. As an unfaithful wife, she is punished purposefully by her brother-in-law, a Russian diplomat who revokes her visa which strands her during the siege. The film’s writers decide that Natasha’s fate is death; however, they do give her a redemptive arc by allowing her heartfelt sacrifices to be in the aid of others.

Ava Gardner's personal copy of the script for 55 Days at Peking. Now in the permanent collection of the Ava Gardner Museum.

In all of these films, Ava portrayed women who dared to step outside of the acceptable roles and behavior of their time. She was not a dutiful, faithful spouse or mother keeping down the home front. Instead, she was a mistress searching for connection; a heartbroken celebrity clinging to happiness; a partner who puts her husband’s freedom and fulfillment above her own; a prostitute caught up in war; and an unfaithful wife who uses her fortune to save others. All of these women had complicated motives and intentions; however, these characters were held to a strict moral code and subject to the anxieties and insecurities of men in post-WWII America. While these women all paid the ultimate sacrifice – death – Ava gave each one a greater sense of depth than what was written on the script’s page. Despite the production code not wanting these roles to be sympathetic, Ava’s skill and talent as an actor makes these characters come alive to the audience, and we collectively feel connected to each one no matter their fate.