'White Liquor and White Lies' details

county's history of moonshining

As long as there have been governments, there have been taxes. And since governments began trying to collect those taxes, people have looked for ways to avoid them.

That's the story of moonshine and bootlegging in a nutshell — man's search for a good drink without the stress of reaching into his pocket.

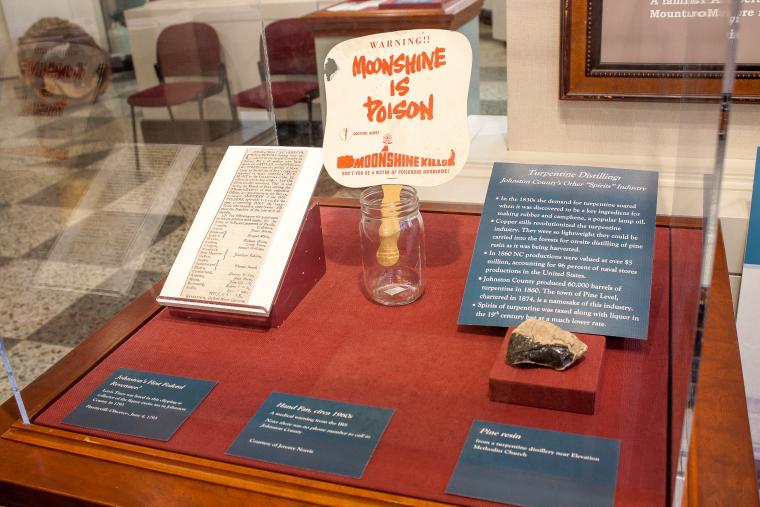

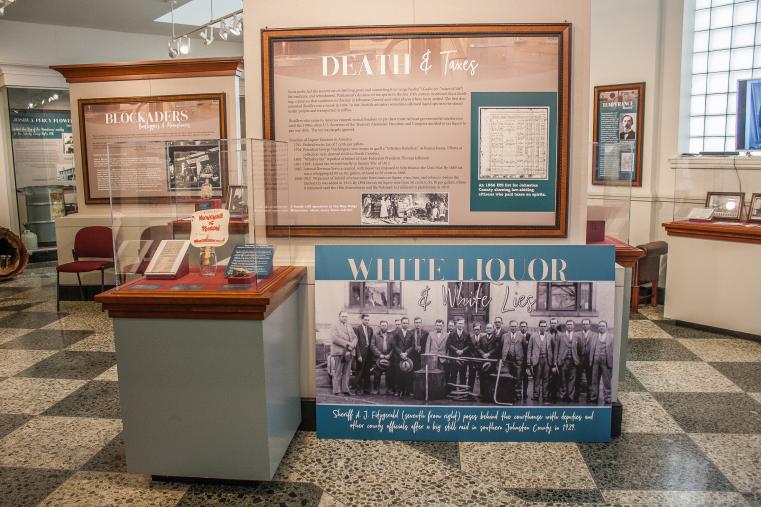

The history of the profession is on display through the end of the year at the Johnston County Heritage Center in their “White Liquor and White Lies” exhibit.

Inspired by Perry Sullivan's donation of a few items from his father, Percy Flowers, Johnston County Heritage Center Director Todd Johnson decided to create a full-blown display.

“I just got into the story and realized it was a very important part of our culture that had never really been displayed or interpreted,” he said. “This is just scratching the surface. We have a fairly small exhibit space.

“It does attempt to tell the story of bootleggers and moonshine culture in Johnston County. We went back to the early days, even before Prohibition, to try to trace the story.”

That's one of the misconceptions about moonshine and bootlegging. While Prohibition made the practice a necessity, the idea actually got its start in Scotland in the 1700s.

“The Scots called it the water of life in Gaelic,” Johnson said. “They learned that they could distill grain for medicinal and refreshment purposes. People started making money on it, and Parliament decided that there should be a tax on spirits. So there was a similar resistance to taxation even before they came over here.”

Settlers brought their stills and recipes with them when they came, and thus, an American tradition was born.

Spirits became such an important part of the colonial culture that, in 1776, local leaders raised troops to send to the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge, near Wilmington, by offering them payment in liquor.

Some of the ledgers are on display in the exhibit.

After the war, there were bills to be paid. Alexander Hamilton had the idea of taxing liquor to retire the Revolutionary War debt.

“It went over like a lead balloon,” he said. “In 1791, the tax was seven cents per gallon. That was just exorbitant back then. By the time of the Civil War, it was $2. We have IRS records for Johnston County that show the few people who actually paid it.”

After the War Between the States, when North Carolina re-entered the Union, the moonshining culture really took root.

“After the Civil War was when bootlegging really became part of the culture here,” Johnson said. “When we went back into the Union, people were expected to pay this tax. And they did not. What blew my mind is when I found out that 90 percent of Federal revenue before the income tax came from taxes on liquor and tobacco.”

Not everyone was found of the industry. The temperance movement sought to rid the country of alcohol. Of course, with so much legal revenue at stake, it wasn't until a national income tax was established in 1913 when the idea really started to gain traction.

One of the steps towards the eventual passage of Prohibition in 1920 was the establishment of dispensaries in Johnston County.

Smithfield's dispensary opened on July 1, 1899 — ironically in the Heritage Center's current location on the corner of Third and Market. The idea behind the dispensary, which was sort of like today's ABC store, was to provide residents a place to purchase, but not consume, spirits.

It was an effort to clean up the town, which just a few years earlier, had nine saloons within a block of the courthouse downtown. There were also dispensaries in Selma, Clayton, Pine Level, Micro and Kenly.

Prohibition is where many of the better known stories began, but the exhibit traces the roots of bootlegging back much farther.

“People think that bootleggers started with Prohibition after World War I, but that's not the case,” he said. “People evaded the taxes from the very beginning. They called them blockaders in the early days.”

The 20th century also gave rise to some of the county's most important characters.

Robert L. Flowers, who was no relation to his more famous namesake, Percy, was sworn in as a federal marshal shortly after the start of Prohibition.

His obituary in the June 17, 1926 edition of the “Benson Review” read that he would often walk through Benson with “a still on one shoulder and a rifle on the other.”

“My grandmother used to tell me a story about when she was a little girl,” Johnson said. “She grew up near Benson, and her grandmother always made scuppernong wine during Prohibition. She would keep it in the flour barrel. She would put a piece of wood in there and a little bit of flour on the top.

“But some neighbor ratted her out, and Robert Flowers came and busted up all of her wine. She said it was like a river going through the back yard.”

The liquor that wasn't spilled wound up impounded at the courthouse, where residents could come with jars and blocks of camphor to prove they planned to use the “white lightning” for medicinal purposes and take home a free jar full.

Of course, no exhibit on the history of Johnston County bootlegging would be complete without a nod to Joshua “Percy” Flowers, who “The Saturday Evening Post” called “The King of the Moonshiners” in 1958.

There are other noteworthy entries in the exhibit, such as a Kl Klux Klan hood and robe from the 1920s. The Klan, in a bit of moralistic irony, was very interested in the abolition of alcohol, going so far as to visit stills to encourage moonshiners to change their sinful ways.

There's also a section of a 1792 will in which John Norris left his still and all of his whiskey to his son, Nathan.

Based on one of the exhibit's displays — a model still made by a student at South Johnston a few years ago — there's still a bit of bootlegging going on in the county.

“Let's just say that the person who gave them the information knew what they were doing,” Johnson said.

Attendance for the exhibit has been good, Johnson said. He only wishes he had more room.

“It's been good,” he said. “We have a steady flow of people coming by to see it. We just need more space, so we can have more stuff up. We're working on that.

“It's one of those almost taboo topics that's a very important part of our history. People like to do things that are a little bit naughty. Moonshine was one of those things that a lot of people did. It was accepted, but it was not. There probably isn't a family from Johnston County who didn't have some family member that was involved in this business.”

You can find this and other articles in the Johnston Now September issue.